Players Seek Challenges, not Easy Practices

Avoid boredom and monotonous, not difficult and challenging.

Coaches hate the word “fun”. They equate fun, and its cousin “play”, with unserious, and they take themselves, their teams, and their jobs very seriously. They cannot tolerate fun or play when there is a championship to win. Steven Kotler in The Rise of Superman, wrote, “If we are hunting the highest version of ourselves, then we need to turn work into play and not the other way around.” Play has value; fun is not a bad word. Play and fun are not unserious; instead, they are more frequently the antithesis of boring.

Coaches appreciate boredom. They value repetition after repetition after repetition. They equate boredom or boring with hard, and criticize players and others who criticize practices or drills as boring because they obviously just want the easy road. They want to avoid challenges. In most cases, coaches are wrong.

Easy and hard have little to do with boring. Monotony is boring. Challenges are the opposite of boring. People have “an inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacities, to explore and to learn” (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Ericsson’s research into expertise and deliberate practice convinced a generation that tedious, methodical, monotonous, repetitive practice was the path to expertise, but his research primarily centered on musicians; No practice activity in sports has been identified as highly relevant and effortful, while scoring low on enjoyment (Deakin & Cobley, 2003; Moesch et al., 2013). Repetitive workouts, exercises, and routines without variation cause boredom (Velasco & Jorda, 2020). As boredom increases, performance diminishes (Velasco & Jorda, 2020). Players do not resist hard work and effort; they avoid boredom.

Players crave challenges. Frans Bosch wrote in Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach, “We learn through confronting something new, rather than imprinting something familiar.” Monotony dulls our interest, motivation, intensity of effort, and learning. As Bosch said, “Variation is the key to efficient coaching.”

I have not attended a college practice in a few years, but based on previous practices, and the information from former players who matriculated to NCAA programs, practices are extraordinarily similar given the large geographic area, population, and background of coaches. If you created a standard template of a college practice, roughly 80% of practices would be roughly 80% the same, give or take 10%. Nearly every practice includes block practice shooting drills, shell drill, pseudo-transition drills for layups and conditioning, and non-competitive practice of offensive sets. The practices are repetitive, and boring.

Now, coaches may or may not agree with some or all of the Fake Fundamentals. The three-player weave may be your favorite drill. Multiple great coaches highlight the importance of the daily shell drill. You may value repetition after repetition of shooting drills and five-vs-zero offense. That is not my style, and I do not think it is the best way to coach, but plenty of successful coaches follow this general format and favor these drills. It is not wrong per se, but it certainly is boring, especially for players who have been coached differently.

Would you enjoy the three-player weave if you were accustomed to Rabbit?

Would you exert full effort and focus in the shell drill if you previously played 4v4 Canada Rules?

Would you get as much from five-spot shooting drills if you previously practiced with advantage shooting drills?

Would you practice with the same concentration during five-vs-zero as during two-minute end-of-quarter execution games?

Coaches argue repetition is necessary, and players must embrace the grind, but boredom directly affects learning. “Boredom is a mismatch between an individual’s needed intellectual arousal and the availability of external stimulation” (Willis, 2014). The brain creates a generalized prejudice against the activities after experiencing boredom (Willis, 2014; Eastwood et al., 2012). I encourage coaches to end activities before they go on too long or become monotonous, even when the players enjoy the activity, as they risk players developing a memory of the monotony rather than an excitement to return to the activity. Even fun, relevant, enjoyable activities can become monotonous when it is the only activity or the activity goes on too long. Players can even tire of playing five-vs-five and actually prefer a drill when five-vs-five goes on too long and loses its challenge or relevance (see the difference in intensity in a tightly-contested game versus a blowout).

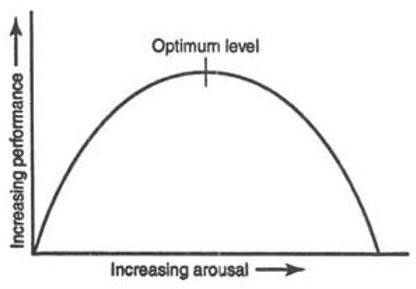

The inverted-U theory is one of the oldest theories in sports psychology (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908). Arousal increases along the x-axis from left to right, and performance increases along the y-axis from bottom to top. Too little arousal indicates boredom; too much arousal indicates stress or anxiety. The inverted U illustrates the changes in performance from poor performance (boredom) to maximal performance (optimal) to poor performance (anxiety). The optimum level is termed a just-right challenge, which is just beyond the players’ current level. Not enough challenge, such as five-vs-zero, is boring, whereas too much challenge, such as executing an end-game play against an aggressive defense for which you have not prepared, causes anxiety. The goal is to spend the most time in the optimal zone, providing sufficient challenges, but not too great that players are frequently stressed and anxious.

Relevance increases engagement and reduces boredom when activities are related to players’ interests or needed to achieve a goal (Willis, 2014). Former players who complained about their boring practices frequently referenced a lack of relevance; they felt the activities did not improve their game performances. For example, one player, who won every fitness test we had and now works as a personal trainer in addition to continuing her basketball career professionally, thought running sprints during practice was boring. She played harder than anyone, and if there was a sprint or conditioning drill she won it, but she also questioned its relevance. Why run for a bad defensive possession instead of practicing the defensive mistake? Why run for missed layups instead of practicing layups? She did not seek an easier practice; she wanted relevance; she wanted to improve. She wanted a greater challenge; running was easy. Boredom is not just being repetitive with practice activities, but using activities unrelated to performance or skill development.

Learning a novel task and overcoming challenges stimulate the brain. The brain does not work as hard once the task is learned and there is no more challenge; the brain gets lazy. The brain works more efficiently, and efficiency is not a player’s friend when trying to improve (Kuszewski, 2011). Increase the challenge once the current level is learned to force the brain to continue making new connections (Kuszewski, 2011).

Instead, coaches embrace repetitive activities as a means to develop the elusive and misnamed muscle memory (Fake Fundamentals), but repetitive activities tend to disengage the players’ brains. Players go through the motions to get through the monotony. Disengaged brains, getting through drills, and going through the motions are not qualities of learning and improvement. The goal is to improve the skill, not to master the drill. Grinding is not learning.

Monotony of training leads to de-motivation and overtraining, which disrupts learning and skill development. Variation stimulates learning and increases motivation. “We learn through confrontations with something new, rather than imprinting something familiar” (Bosch, 2015). How can you confront your players with something new to stimulate their learning? The three-player weave is not the answer.

Boredom is a common, negative emotion related to monotonous activities (Velasco & Jorda, 2020). We teach players to embrace the grind, but getting through a drill is not learning. As Kobe Bryant said, “It’s not about the number of hours you practice, it’s about the number of hours your mind is present during practice.” Boredom is not the path to mastery, but the road to stagnation and premature plateaus.

Not every drill must be new or creative. In fact, players are bored by some creative drills because they fail to see the relevance. I use very few drills. My practices start with the game or activities that include some constraints affecting the skill execution in games. For example, we play tag instead of straight-line dribbling drills because the movement, the evading, the interactions with opponents, and more are representative of the environment in which one makes a move in a game. Of course, playing the same tag game every day gets monotonous too, even when every player loves the game. Therefore, we change tag. We switch from team tag to team tag relay; from individual tag to individual tag in small groups. I also keep the games short, even when everyone is smiling and going hard. We will return to the games, but I do not want to overcook the activity in a single practice.

My practice template actually varies very little. On any given practice, you likely will see a dynamic warmup, tag or keep away, a simple shooting drill, one-vs-one full-court, a transition game, a small-sided game, a post/guard breakdown with one-vs-one or two-vs-two, five-vs-five half-court, five-vs-five full-court, and a more involved shooting drill. One-vs-one full-court is really the one everyday activity that does not change often; there are a few variations, but we probably use the most basic one over 80% of the time.

I rely on competition more than novelty to prevent monotony and increase engagement. Within the general segments, there are different versions of drills, different starting points, different scoring systems, and more. We play three-vs-three in dozens of different ways throughout the season when considering starts, time, scoring system, rules, constraints, manipulations, and more, but in the end, it is a version of three-vs-three. In the one sense, it is a repetitive, monotonous activity, as we play three-vs-three maybe five times per week. However, players are rarely bored by three-vs-three because it is competitive, the interactions with opponents and teammates mean the game is never exactly the same, and the different modifications change the game slightly every day.

I am not overly creative, nor seeking to be novel or show my brilliance. I simply see what we need to improve and use a rule or scoring to change the game and emphasize the specific skill. When we are not rebounding, we count offensive rebounds as points. When we are not cutting or our defense is not physical, we play no dribble. There are some standard games. However, we could play out of the start of an offensive set or require a post touch or whatever we need to practice or I want to emphasize. In that way, one game — three-vs-three — can be almost anything, and the one game avoids becoming monotonous.

James Clear wrote in Atomic Habits, “At some point it comes down to who can handle the boredom.” I would argue this misses the point. We play sports. Players enjoy challenges. If players are bored, something is wrong in the environment, whether the activities are too repetitive and monotonous or the players fail to see their relevance to their improvement and performance. Players do not want easy or unserious. They want to be challenge. They want to improve. They want to play. They just do not want to be bored.

References

Deakin, J.M. & Cobley, S. (2003). A search for deliberate practice. An examination of the practice environments in figure skating and volleyball. In: Starkes, J. & Ericsson, K.A. (Eds.), Expert performance in sports: Advances in research on sport expertise (p. 115–35). Human Kinetics.

Eastwood, J., Frischen, A., Fenske, M., & Smilek, D. (2012). The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention perspectives on psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 482-95.

Kuszewski, A. (2011). You can increase your intelligence: 5 ways to maximize your cognitive potential. Scientific American, 7, 1-8.

Moesch, K., Hauge, M.L.T., Wikman, J.M., & Elbe, A.M. (2013). Making it to the top in team sports: Start later, intensify, and be determined!. Talent Development & Excellence, 5(2), 85-100.

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Velasco, F. & Jorda, R. (2020). Portrait of boredom among athletes and its implications in sports management: A multi-method approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 831.

Willis, J. (2014). Neuroscience reveals that boredom hurts. Phi Delta Kappan, 95(8), 28-32.

Yerkes, R. M. & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18, 459-82.

The Athletic has done a series articles on the “new” training taking the NBA by storm called CLA or Constraints Led Approach which replaces block practice with more variable practice in which the coach designs a game like drill to focus on skill development. They cleverly call it repetition without repetition.

All I could think to myself is that seems very similar to a guy I’ve been reading for the past 15 years (maybe more) and his approach to coaching basketball.

You’ve always been ahead of the curve on this stuff, it’s a shame you don’t get the credit you deserve.

Amen. Weightlifting is by its nature, somewhat monotonous (like middle-distance running). However, I try to manipulate the lifts, reps, sets, point of emphasis in every session, without creating a free-for-all where no-one remembers the original purpose of why we're there: to lift more weight above our heads.

Where I do change things every session, is in the warm-up: movement patterns, use of games, different structural-integrity exericses. Fun is key here. This also acts as a transition from work/school to training with purpose.

(n.b.The only time I've used the word 'grind' in the last ten years is when I wrote my novel, Stone and Water (the Celtic women used a Quern stone to grind the corn. Hence the term, 'The daily grind.')